The Fatigued War

I’m standing in a rather derelict complex of ground-level buildings. They have not collapsed yet, but they have seen better days. Explosions cut through the silence as I’m drinking some water. We’ve just finished unloading a van full of food and humanitarian aid and the kevlar vest is keeping me hot even though it is February. “Let’s go inside. The risk of shrapnel is lower there.” says one of the locals in Ukrainian. He’s right. Even though Kherson has been liberated a few months prior, it is still getting shelled daily and people are getting killed by mortars, artillery, or rockets nearly every day. Russians are dug in just across the river and these are most likely desperate attempts to demoralise the population. From what I have seen during my two weeks in the country those attempts are worthless. Ukrainian resolve has probably never been stronger. But let’s start at the beginning which is at the border since my visit has taken me across half of the country.

I got in touch with this group of people that have been helping whomever they could, delivering food and necessary supplies since the first day of the invasion in 2022. They have since formed an organisation called Koridor UA aimed mostly at being the connection point between Czechs willing to help and Ukrainians needing the help. I figured it would be an interesting aspect of the war I have not covered yet so I asked if I could spend some time with them. They’re based in Prague, Buchach in the Ternopil Oblast, Odesa, and Mykolaiv. I figured I’d start west and head east. The founder of the organisation Matouš is meeting me in Uzhhorod on the Slovak border. It is a lovely city rich with history. It used to be Czechoslovak, Hungarian, and Soviet and now it is Ukrainian. The reason we’re currently here is that Koridor intends not only to be the constant humanitarian aid delivery company, but they also want to help raise funds, organise fundraisers and pioneer other projects which would help the civilians struck by war.

The plan for Uzhhorod is to organise a three-day theatre festival featuring Czech and Ukrainian artists aimed at raising funds for more humanitarian aid. And for the festival to take place some meetings with local influential people have to happen. Granted, this isn’t what I first had in mind I’d be doing when I entered a war-torn country, but it was rather interesting to spectate. Firstly we met with the director of the Mariupol theatre. Yes, that theatre which was famously bombed during the infamous siege of Mariupol. It contained hundreds of civilians including women and children hiding from the Russian army trying to overtake the city. The destruction of the building has caused over 600 civilian deaths in a single strike. The remainder of the theatre staff that managed to escape the city in time before the city was lost has since been working from the building of the theatre of Zakarpattia.

Next up were the local military council and the regional council of Zakarpattia. The military has to know whether there is any activity happening especially late at night. The regional council is led by a man named Volodymyr Chubirko. A serious and busy man. He’s closely working with his Czech counterparts in terms of cooperation. Even though Zakarpattia has not been directly hit by the ongoing war it is still very much affected. Hundreds of thousands of IDPs (Internally Displaced People) live in the region and there is no work for them here. Many lack proper accommodation so the regional council does what it can to give everyone a roof over their heads, food and some basic income. It is a rather interesting meeting. His Czech is not too bad. Seems like some cooperation between the Zakarpattia region and Koridor UA might be possible. All seems on track with the festival. But that is not what I’m here for.

One of the volunteers named Denisa is headed for the Buchach base in the Ternopil region whilst the rest of the group plans on crossing the border and heading back to Prague. I accompany Denisa and offer to help with the drive. We’ve got a long road ahead of us. It is not that far to reach Buchach, but the state of the roads and the lack of motorways make it a seven-hour road trip. Oh, and the radio isn’t working. Plenty of time to chat. Denisa has been with Koridor for a few months now so I ask her the obvious questions which I’ve already asked Matouš the day before. It makes sense to get more points of view.

The entire organisation is voluntary. Nobody is getting paid. All of the funds raised are seemingly being immediately put into the organisation to pay for diesel, bills, van repairs, and other necessities. Matouš has told me before that Koridor is not here to take care of freeloader volunteers. Sort your stuff out and then you can come help. Don’t be a burden, be useful. It makes sense. The money is running thin day by day. The post-invasion war has been going on for over a year and many people are tired of hearing about it. Crowdfunding and donations have dwindled.

We get to Buchach late at night. The drive was made even more interesting since the van was loaded with what seemed like a ton of flour and dozens of computer cases and screens. That combined with the fact that the brake tubes are seriously rotten resulting in annoyingly sluggish brakes at the brink of breaking at any point made it rather risky. We made it though. Through the Carpathian mountains, around the military checkpoints, past a burning field and all of that without a scratch. The “base” in Buchach is a house on the outskirts of the town. It looks pretty nice from the outside and it’s heated on the inside. Nothing to complain about. I even got my own room to sleep in. Far more comfortable accommodation than I expected. I guess my bivvy and the Bundeswehr sleeping mat were unnecessary extra weight in my pack.

I meet the guy running the Buchach branch of Koridor. A Slovak named Martin who has been helping on the border crossing in Vyšné Nemecké since nearly the start of the invasion. A calm and quiet man. Collected, and organised, yet with a sense of humour. It is clear he wants to help whenever and however he can. He and Denisa are accompanied by yet another volunteer Noemi. An elementary school teacher from Prague who is clearly the funny one in the group. It was rather rare not to see her smile or laugh.

The main aim of the Buchach HQ is to distribute aid and food to the local IDP population. For that, the organisation is using a repurposed warehouse on the other side of the city. It is situated in the workshops of a local car mechanic school. The walls are decorated with multiple schematics of all kinds of car parts, systems, and inner workings. Engine blocks, chassis, and axles are on display all tucked away in one of the corners. One of the rooms is filled with neatly organised piles of clothing, shoes, school bags, diapers, toilet paper, cleaning products, and even strollers. Shoes and clothes are divided into adult and child-sized. Diapers are divided into sizes 1, 2, 3 and adult. There is a desperate shortage of size 4 or 4+ which is the size a child needs for the longest period of their growth. The other room is surrounded by pallets of food. Bags of flour are accompanied by multiple kitchen scales and buckets, same with salt and sugar. You can see piles of ramen noodles, beans, stacks of canned meat, wafers, sweets for children, patés and other long-lasting ingredients. The last room stores non-edible necessities like head torches, PMRs, lighters, power banks, medkits, trauma kits, vitamins, insulin pens, decommissioned computers, or medication. The room is decorated with a large map of Ukraine on the wall which is hand-stamped by children indicating which cities or regions they’ve run away from.

Each IDP gets a package containing dried milk, 500g of pasta, 3 cans of meat, a bag of rice, a bag of beans, ramen noodles, oats, 500g of sugar and salt, 1kg of flour, 2 patés and 2 rolls of toilet paper. If you have got children in your household you get some extra sweets and wafers. A few months ago it was a decent package that could help a family for a while but the supplies and funds are running low now. Koridor has to ration, everyone does. So each package is tied to an IDP’s personal ID number and passport. If you can’t provide those you’re not getting a package. And you can only get a package once every three weeks. Imagine living off that list for three weeks.

There was one older woman in her sixties, maybe seventies, who came in on a Wednesday which wasn’t distribution day. She didn’t have an official IDP ID and so she couldn’t get a packet. My Ukrainian is spotty at best so I only understood a fraction of what was said, but she was visibly angry at the whole process. If it was up to me I’d have just given her the package but luckily it isn’t up to me. Martin later explained to me they have to protect themselves from people wanting to exploit the system. I get where he’s coming from. Supplies are running low and they are not being replenished fast enough.

The way these packets are given out is scheduled. Tuesdays and Thursdays are distribution days. From 10 am to 1 pm, the local IDPs can come to the warehouse with their documents to claim a packet and search through the piles of clothes, shoes and other items to grab what they need. It doesn’t take long for a queue to build up at the entrance. Regardless of how cold it gets. And it can get horribly cold at times. The Czech volunteers are assisted by a few local kids who help with translation, loading/unloading, packet prepping and organisation. A jolly bunch of four boys and girls who keep the mood rather happy even through the weight of the situation.

Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays are delivery days. Martin makes a list of nearby villages and towns, contacts the local mayors, gets the numbers of IDPs in each village and once the van is loaded we head out. Ukrainian roads leave a lot to be desired. Pre-war corruption and the current repurposing of funds towards the military have ensured that the roads often feel like offroading. I feel bad for every car’s underside. Getting anywhere takes a whole lot longer than it should. We visit a few villages, meet the local mayors, and hand over the packets for which the paperwork must be filled out diligently. Everything is recorded and tracked. There is one village named Dobropole in which the mayor wasn’t answering his phone. We took packets there anyway just in case. Turns out he’s on the frontline fighting and he has no deputy to cover for him. A harsh reality of a country having to mobilise civilians into the ranks of soldiers.

After a bit of driving around and asking multiple locals, we made it to a house which has phone numbers for all the IDPs in the village. A humanitarian van seems like an event here since every villager in the vicinity has come out of their house to observe. Once all of the IDPs come and collect it is time to head back home. Finally. There are four of us and the van seats only three people. I’ve been freezing my ass off in the back of the van among the food for hours at this time. It was well worth it though.

On the 23rd we load up the van with more packets, a refrigerator, a washing machine, and a microwave and head to Zolotyi Potik. A small town about an hour south of Buchach. The road is absolutely terrible. I’m surprised the van made it in one piece. Once we’re there we park next to this repurposed hospital housing nearly 40 people who ran away from the war in the east. Many of whom are old, bedridden, or children. The building is old. Very old. So old, the electrical wiring has become a safety hazard. That is why we’re here. Martin is experienced in this stuff so he’s been coming here in his free time to help with the wiring, sockets, switches, and junction boxes. Finally, the wires are grounded, the appliances don’t shock random users, and the sockets are where necessary eliminating the need to run an extension cord across the entire hallway.

Martin clearly cares for these people. I managed to capture a beautiful moment between him and this little Ukrainian boy playing on his phone. Slovaks get a bad rep due to a large amount of the population usually polling pro-Russian and xenophobic towards Ukrainians. He's proof that there are many decent Slovaks who see the reality of the situation. Many do their best to help as much as they can.

There is this communal kitchen where all the residents sign for their packets. We are greeted by a local woman in charge of things named Olha Stepanivna. She is quite possibly the happiest Ukrainian I’ve ever met. Her ear-to-ear smile is on for the entire time of our visit. She is clearly overjoyed that someone is there to help. The boys unload the fridge, the washing machine, and the microwave and put them in place. The residents are visibly happy. This must mean a lot to them and after seeing their facilities I know why. I’d make every doubter live like this for a month or two. Their view of things would probably shift towards a more generous side of things. I feel terrible for the children having to live here. I know they can easily adapt, but they shouldn’t have to in the first place.

All of us are invited to sit in the kitchen, drink tea, eat their delicious pierogi and just have a lovely time. The locals even sing us a song. We tried to decline the food offer saying we can always buy our own but they insisted. As I’ve said in my 2018 story. The least fortunate tend to be the most generous. Later in the day, the locals give us a tour of their castle ruin, we exchange hugs and it’s time to head back. I need to hurry to catch the last bus to Ternopil from where I get a train to Odesa to meet the other half of the Koridor UA volunteers.

I meet this soldier on the Ternopil platform. He’s telling me how he’s headed into Bakhmut to help his brothers-in-arms. His face is scarred and obviously not yet healed. Looking at a photo he’s showing on his phone I see his face completely covered in blood after being hit by shrapnel. He’s lucky to be alive. But he said he snuck out of the hospital. He knows what his fellow fighters are going through and can’t bear to leave them alone. I curse myself for not taking his picture once I’m on the train, but my bag was so damn heavy I was happy I could stand when we talked. The train is old, but like every other overnight train in Ukraine, really bloody comfortable. I slept like a baby which is a weird analogy. Babies rarely sleep at night…

Odesa is a very different experience from Uzhhorod or Buchach. The military presence here is vastly higher. Anti-tank barriers are everywhere, military checkpoints are plentiful, many windows are boarded up, diesel generators line up in the streets, and the whole city is ready for an invasion from the sea. But once you look past that the city lives like no war is going on at all. People go on about their lives, shops are open, trams and buses are running on time, civilians keep going to work, restaurants serve food, markets sell souvenirs, and joggers populate the beaches.

Odessa is beautiful. Just beautiful. Especially the historical UNESCO centre or the seaside. Koridor’s base is in a small flat near a military hospital, so the soldier presence is heightened in the area. The Odessa branch of Koridor UA is being run by a young guy named Richard. He is only 23 years old, seriously dedicated, and incredibly busy. There is a lot on his plate and it seems like he could really use an assistant. But the deliveries are running smoothly and the admin seems done to the tee. I feel like he knows what he’s doing. He’s got this on-and-off personality where he seems to relax at one moment and then suddenly goes 100% the next. It reminds me of my youngest brother who gets this tunnel vision once he focuses on a task. Nothing can derail him from what he’s tasked himself with.

The other two guys in the flat are Jan and Karel. Two tall, skinny, long-haired and bearded dudes. I almost thought they were brothers at first glance. Only after a few hours, I started noticing the differences and now they seem like two opposites to me. A calm, collected, and often philosophical Karel next to a hyperactive, music-driven, enthusiastic Jan. They seem to complete each other when working together. I went on to have some really interesting philosophical conversations with Karel. Some issues we agreed on, and some we disagreed on.

The first few days in Odessa were not particularly exciting in terms of Koridor’s activity. The 24th was spent searching for new tires for one of the vans since one of the old ones kind of exploded a few days back. We went to this car-part market which was pretty interesting. It felt like a small town within a city with every single car part you could think of. Imagine London’s Camden market multiplied a few times and only aimed at anything a car might need. Even the most obscure bits were available. Jan and Karel bought a pair of tires and before having them fitted we were approached by the owner of the workshop telling us the tires are definitely a bad choice. They lacked the “C” specs needed for a cargo van. A few deals happened here and there, and a few tires were discussed before the guys finally settled on a pair. The next day was spent in a military hospice attending a battlefield medical course. I noticed the guys were woefully unprepared for a crisis situation. They all shared a single medkit, maybe two tourniquets between all of them and no formal training or even basic triage. Hopefully, this training has taught them some basic principles of survival on the battlefield. They definitely need to get proper medkits and enough tourniquets to prepare for the worst though.

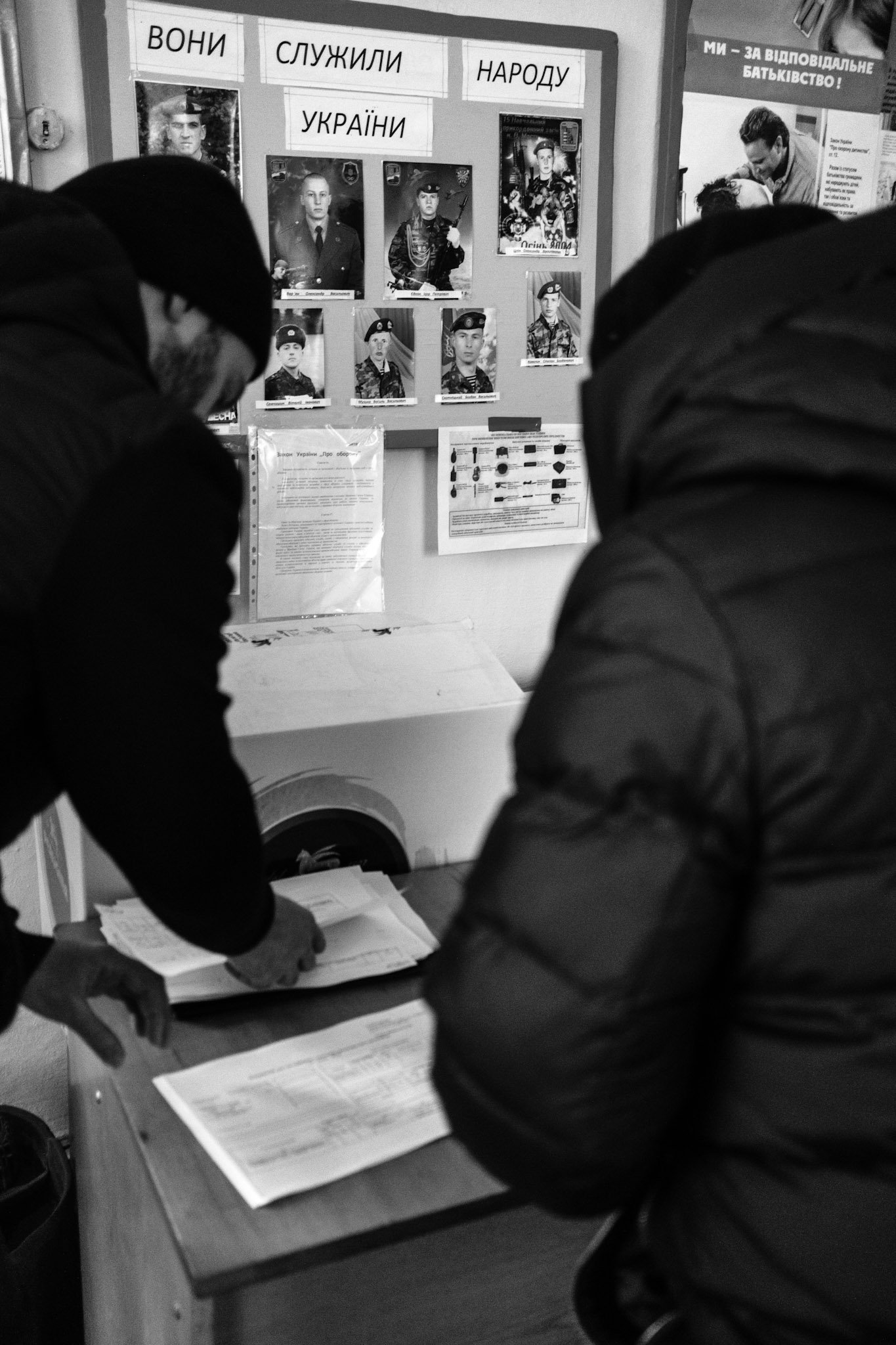

The third day was a continuation of the medical course which I opted out of. It wasn’t particularly interesting photographically and I wanted to see the city a bit. I walked for at least six hours just taking the city in, learning Cyrillic along the way and getting some images of civilian life. A few interesting events caught my eye. The first was an event near the National Academic Opera. It was a bunch of people wearing Ukrainian flags and celebrating. There was a large sign saying “дякуємо зсу” (Thank you ZSU) made up of photographs of what I figured were servicemen and women currently in the military. ZSU is the abbreviation for the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

The second event was a lot more sombre. It was a pop-up memorial for the fallen soldiers in a park near a church. Large photographs with ranks, names, dates of birth and death, and short obituaries dedicated to those who gave their lives to protect the country. Many were decorated with flowers, candles, and notes. Some locals were weeping whilst reading about their loved ones. It was an incredibly sad event. Many of the pictured soldiers were young and had their entire lives ahead. Some were older and had left families and children behind. Needlessly killed.

The next day Jan and I head out to Mykolaiv to distribute food. We leave early in the morning before the Sun is even up because it takes at least two to three hours to get to Myko. We pick up Andrei on the way. A local volunteer living in Odessa. He used to be a dancer before the war but decided to aid the civilians in the best way he could. He knows people and can get things done. I immediately felt like I knew the guy. He seems kind, often happy, chatty, and full of stories. He kept recording video messages and Instagram stories in-between gaming on his phone during the drive. I’m a little sad I didn’t have my speedlight and my softbox with me, because I’d love to take his portrait.

Mykolaiv is on a whole different level compared to Odesa. Many buildings are damaged by shrapnel, explosions, and shelling. Water is scarce. Electricity is not guaranteed. The streets are lined with destroyed shops, broken windows, and shelled roads. Buildings are surrounded by trench systems, firing positions, makeshift bunkers and sandbag barriers. This is a city ready to be invaded. It actually was. Russians have made it to the outskirts before being repelled.

The warehouse has also clearly been hit by a shrapnel bomb. Many small holes litter the walls and the gates. Some bits of shrapnel can be seen lodged into the holes slowly rusting away. It is a large warehouse. Dozens upon dozens of palettes of food take up the majority of the available space. Apparently, most of it belongs to this local politician Vasyl (or Vasil, I only ever heard his name spoken, never seen it written), and he loans it to the Koridor guys for free. In turn, they help him deliver his supplies to the local villages as well. Today we need to take seven vans full of food to a village called Shevchenkove roughly 30 minutes away.

We only have one van though and it is a lot of food, so Jan calls a local man named Ivan and asks for his help. Once we load the van with bags of flour and boxes of food we head out. We drive past multiple barricades built to slow down the traffic into a single file, through a checkpoint where we’re inspected by soldiers and then towards the village. Once we arrive there is a group of locals ready to help us unload the van. It's mainly elderly people, grandmas, and grandpas who are carrying the heavy stuff. Everyone helps. Everyone does their part. The building we’re unloading at is a local library heavily damaged by war. This village was actually occupied by Russians not long ago. After unloading the elderly women proceed to clean one of the rooms. There are gravel and brick fragments everywhere. The ceilings have partially collapsed and the walls have been infested with an unhealthy amount of mould.

Coming back to Mykolaiv we get inspected once again by the military. This time we load nearly two tonnes of food in the back. The van clearly wasn’t built for this. The tires seem like they’re about to burst and the back of the van is seriously close to the ground. It’s a slow drive to make sure we make it. Once we pass a carcass of a dead dog on the side of the road I know we’re halfway there. That dog would become a bit of a distance marker for us on these repeated trips.

Upon arriving we’re once again helped by the locals. This time it’s 50 kg heavy bags of flour, which two of the locals insist on carrying solo for some unknown reason. We keep telling them to take it easy but they don’t listen. Eventually, one of them twists his ankle under the weight and has to tap out for a while. The women asked him whether showing off was necessary. It clearly wasn’t. But to my surprise upon the last arrival, he’s back on his feet with multiple heavy boxes in one hand and a pierogi in the other one. I guess his “tough guy” image will stay untarnished.

It’s been a tiring day for all of us. Jan is staying behind to sleep at Ivan’s while Andrei and I head back to Odessa. Andrei doesn’t drive so it’s up to me. The best part of that entire drive was the fact it was pitch black and almost everyone is using their high beams. I was lucky I kept the wheels on the road. But we made it in one piece. The next day we headed to Kherson.

Karel and I left Odessa in the morning again to meet up with Jan in Myko. There we filled the van with food, toiletries, and cleaning products bound for Kherson city. That place is right across the river from the Russians who shell it on a daily basis. Time to get our body armour and helmets on. A few kilometres past the “Kherson Oblast” sign right next to a completely destroyed and bullet-ridden petrol station we link up with two more journalists from Czechia who follow us in their car. Jan is visibly nervous. He wants to get in, unload everything, and get out as fast as possible. The longer we stay the higher the chance of getting hit.

The landscape has changed significantly. Buildings are completely shot up and destroyed, rooftops in the city are destroyed by bombing, the roads have holes in them from all the explosions, and many windows are non-existent. We drove past an obliterated bus stop that had been hit by a rocket that killed 5 people and injured over 20 more just a day before. Russians may have left the city, the war, however, hasn’t.

After a bit of searching, we finally find our spot and begin unloading all of the cargo. Many locals come to help and to make the process quick. The building is filled with clothes, food, toys, sanitary products and even walkers for the elderly. It seems like a lot of stuff, but the woman in charge tells me that one day of distribution makes it all disappear. There are still lots of civilians living in the city.

We’re invited for tea and some biscuits. The lady in charge of the warehouse goes on to tell us how it was living under Russian occupation. She tells us how even though now they have to rely on outside help for food and supplies, they can at least get some. Apparently, it was hell to live under the Russians. Food was nearly unattainable, basic needs weren’t met and the ever-present fear of being killed hasn’t made it any easier. She was happy, joyful, and constantly smiling. Because even though their current situation was horrendous, it was leagues better than what it was during the Russian occupation. It made me think of all the people across the river in the areas still controlled by Russia.

We finished pretty late so we were looking for a place to stay in Mykolaiv. Luckily Ivan has offered his house to the three of us. He’s helped us tremendously. Ivan is a man living near a rail station in Mykolaiv who speaks pretty good Czech due to living in Czechia in the past. He’s got a whole group of people who take care of each other in his area. I’ve mentioned how scarce water is in Myko. He’s built this large system of tanks and taps so that everyone in his area has access to drinking water whenever they need it. Whenever we visited his place we were greeted with food, tea, cake and water. This time we were to sleep at his place.

Apparently, if you sleep at a Ukrainian’s home he feels obligated to feed you as well. So he made a few phone calls saying he’s got three stranded Czechs who had just been to Kherson with humanitarian aid. Suddenly a woman named Tatiana came with a pan full of freshly made borsch, another person brought a pot full of what looked like risotto and a third one came with some pasta. We went over to his house, sat down in a small cabin in his garden which also housed his sauna, set the table, and the party was about to start. A few bottles of what seemed like schnapps or vodka appeared on the table next to the food along with shot cups and a few more guests. Andrei eventually arrived as well and it was clear that Ivan and Andrei are close. The borsch was wonderful as well as the paté on the baguettes. Guys were getting drunker and drunker whilst I just watched and photographed. I was told that nobody can say no to a shot of vodka from a Ukrainian. Luckily Ivan understood that I don’t drink. Even though he did threaten me at least six times with me disappearing underneath his mother’s flower beds. He’s emphasised the fact he’s got a pick and a shovel ready for me if need be. I’m sure he was just joking. Right? I mean, we did have a good laugh about the whole thing.

The next morning he needed help with getting water to his house from the tanks. So I drove the van with Andriushka, Ivan’s right-hand man. We loaded up a 1000-litre tank and started filling it up. It took a while but once that was done I drove back to his house Jan and Karel took over to empty the tank into his in-house tank. Meanwhile, I was invited over for breakfast by his mother. A sweet older lady who makes wonderful breakfast and delicious linden tea. We had a nice chat about her children, her flower beds, and March 8th. Apparently, it is a sight to see. She says I have never seen this many flowers in one place in my life. Seems like they take women’s day very seriously. She reminded me of my late grandmother in the sweetest ways. A quick morning birthday celebration including a giant inflatable dancing bear and a lot of hugs later we head back to the warehouse to load up for our next delivery.

This time the destination is the small town of Mykolaivske. The entry to the village is lined with firing positions overlooking a large field. The field itself is surrounded by signs with “міни” (Mines) written on them. It looks like a defensive line should the Russian army take Kherson again. We drive around for a while before we find the warehouse and the man in charge. Three trips in total which add up to a little over four tonnes of food are delivered to a small theatre with the help of a group of local men. Each trip has to be through the same military checkpoint we passed a few days back. The guys there already know us which makes the whole ordeal that much quicker. Time to drive back home to Odessa.

Andrei has asked me to accompany him and Karel the next day. He’s put a few boxes of gummy bears and Lego sets into the back of the van and we drive to a local shelter for children with special needs. He’s organised a little event for the children to make their day a little better with the help of a local magician also named Andrei. Once we arrive and the children are seated he begins performing classic tricks like the disappearing ball, colour-changing scarves, ropes and metal rings and the children absolutely love it. They can’t believe their eyes, they’re laughing, shouting, waving, and just having the best time. Unfortunately, I can’t share their images due to privacy reasons but their laughs are some of my favourite images from this trip. Andrei and Andrei surely made their day amazing.

The last thing on the programme before my departure was called Magirus. Imagine a massive fire truck, but painted grey and repurposed as humanitarian aid. The cabin can take more than six people and the back can either carry up to four tonnes of cargo or serve as a workstation for a doctor, a place to sleep, a workshop, or anything they’d need. They’ve built in a sink, a water system, solar panels, a Starlink antenna, wifi, generators, and charging stations. It is called a “mobile point of un-breakability” and it should serve the towns and villages without access to electricity, internet, and heat wherever it will be needed at the time.

Matouš has driven it into Odessa from Prague for the last few days and it has just arrived. There is still a lot of work needed though so we take it to a local truck repair warehouse to get to work. Pavel and Lukáš, two Czechs start working on the ventilator whilst Matouš and I attempt to work on the electricals in the back. We do as much as we can that day but it goes by fast. Fortunately, the local named Alexander, who’s going to apparently be in charge of the truck, knows what he’s doing. Looks like Magirus is in good hands.

I have spent two weeks with the guys and girls from Koridor UA and I’ve learned a few things. They have the will to help, they have the know-how to help, and they even have people to help. But they are running out of funds to help. War fatigue has reached everyone. People not currently in Ukraine have grown tired of hearing about it. Support has been getting smaller and smaller. Certain things seem like they could be improved. There is an enormous amount of admin and communication work and it would help Matouš and Richard tremendously to have someone offload some of the responsibilities. They constantly seem to be working at a 100% capacity and it feels like it is not sustainable long-term. But who else is going to help if not them? And it is more than obvious that their help is not only needed but tangible. Koridor is actively improving the lives of many civilians struck by war. Just as I’m typing this there is a large truck loaded with hundreds of windows bound for Ukraine to replace those destroyed by war. Or there is currently a well being built in a local animal shelter to ensure access to water which has been made possible thanks to a crowdfunding campaign made by Koridor.

If you’ve made it this far I’d like to thank you and tell you the same thing I said at the end of my last story from Ukraine.

Every little bit helps.

If you can, help. Either financially or in any other way you feel like you can. Donate unused clothes, a computer, volunteer if you can. Or at least share the story and aim it at people who can help if you personally can not. And I’m not just talking about Koridor UA. If you know of any other humanitarian organisation volunteering in Ukraine, help them if you can personally afford it.